Your phone camera is your best camera, because it's always with you. When people say this about mobile photography, or iphoneography as it's also called, they're usually talking about snapping those unexpected moments: a man in a banana suit on his way to work; a celebrity involved in a punch-up; or maybe just a beautiful sunset.

Certainly, mobile photographers are much more prolific than average amateur "big camera" enthusiasts. They have their photographic brains switched on all the time, looking for possibilities. And the ubiquity of these cameras, combined with their unobtrusiveness, have made them particularly effective at capturing candid moments in public spaces.

But, for many, the initial snap is just the start. It's the raw material for a new creative process. Most mobile phone cameras take very dull photos. But it doesn't matter, because there are hundreds of apps to help you turn them into something amazing. And that's what's really at the heart of it. Costing pennies, mobile photography apps give you the creative power of Photoshop, and more besides, without being tied to your desk. This makes mobile photography incredibly liberating for the creative photographic spirit. Suddenly, every free moment is an opportunity to both take and craft images. These apps have accelerated the creative process, as well as allowing you, quite simply, to be more creative, more of the time, for less money.

Instant gratification

The ability to show your images to the world on platforms such as Instagram has made mobile photography an incredibly vibrant genre. A few years ago, I might have taken the world's greatest photo, but it would be destined to sit unseen on my hard drive – and that wouldn't have given me much of an incentive to take more. Of course, I could upload my big camera photos to photo-sharing websites such as Flickr, but that would mean shuffling back to my desk, connecting cables. Sharing via mobile phone is hassle-free. Your latest creation can be exhibited to the world immediately – and people can give feedback straight away.

People love getting comments about their photos and take great inspiration from the images of others. It's little wonder, with such a vibrant web of personal exchanges, that the genre has been booming, resulting in millions of people taking great photos every day, and experimenting (or "appsperimenting") with their images in highly creative ways.

The importance of apps for mobile photography means the genre is characterised by, and criticised for, highly processed images that can bear little connection to reality. But big camera photographers distort reality, too. Before they shoot, they choose shutter speed, aperture and ISO to achieve their desired effect. Many photographers tweak their images in Photoshop. So where does this idea of objective photographic reality come from? We see reality all the time through our eyes, so it's nice to take a break from it.

Who's taking the images?

At the last count (September 2012), Instagram, the largest dedicated platform for mobile photography, had 100 million users worldwide and hosted 4 billion photos. Facebook hosts far more photos (around 140bn) but not all are taken with mobile cameras. More significantly, perhaps, the second most popular camera on Flickr – which caters for all types of camera – is the iPhone 4S, just ahead of the iPhone 4.

There are other dedicated mobile photo platforms, such as EyeEm and Starmatic, but Instagram was the first of its kind and has built up a critical mass of users that makes it difficult to challenge. Had Flickr launched a mobile app a couple of years ago to integrate with its online archive, Instagram might never have existed.

A large number of mobile photos are snapshots of daily life – people simply Facebooking their lives – but people are doing a lot more with mobile photography nowadays than simply taking photos of their birthday parties or their cats. Having discovered they now always have a camera with them, that there is very little cost involved and that they can interact socially through their photos, millions of people have taken up photography through their smartphones as a creative hobby.

Suddenly, thanks to the social platforms, photography has a purpose. People have started taking more aesthetic photos that connect (thanks to hashtags) with complete strangers across the globe. What's more, the apps have released enormous creativity in people who might otherwise never have got involved with photography.

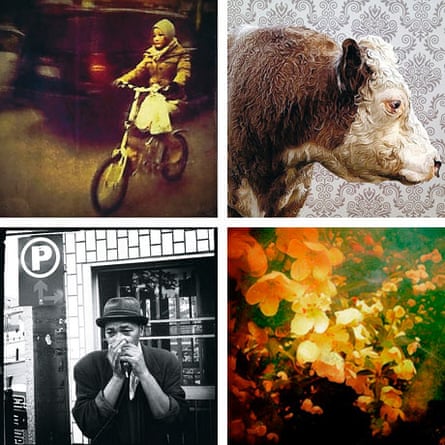

Pioneering online forums such as iphoneart.com and wearejuxt.com are showcasing some amazing mobile photographers and artists (see images below) and are leading the way in a new genre of photography. Other groups, such as instagramers.com, have taken mobile photography offline, with more than 330 regional groups worldwide organising regular photo walks and meetings.

Where does mobile photography fit?

Traditional photojournalists have most to fear from mobile photographers. If something dramatic happens on the street ... sorry, someone's already there taking a photo of it. Your average citizen photojournalist won't compose as well as a professional, but they will be on the spot to capture the moment and be able to publish immediately (heavy processing has no place in good photojournalism).

With commercial photography, the need for high resolution and impeccable light-handling makes phone cameras completely inadequate. Resolution in fine art photography can also be an issue, but, in theory at least, the high-end aesthetic photography world is not concerned with kit – just results. As mobile cameras deliver increasingly higher resolution photos, the results can be printed ever larger.

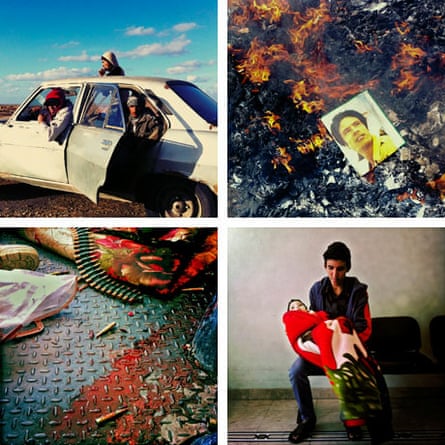

Mobile photography can be very good at street and editorial photography. Mobile photographers can get close to their subjects and not be recognised as a photographer, allowing them to get more authentic images of people. Michael Christopher Brown recently produced a compelling photo essay on the revolution in Libya using only an iPhone (below). Although he was criticised for overprocessing his images in Hipstamatic, shooting on the iPhone gave him a level of access prized by professional photographers.

Mobile photography and business

Businesses have realised that mobile photography, through Instagram, provides a new channel for effective visual advertising, and are making use of the social media platform in two ways. The first method is to open an account under their own name and simply feed photos to their followers. The second, more controversial, way is to hire Instagram users with a large number of followers, so-called superusers, and get them to take photos featuring their products.

To avoid having a reputation as a platform full of covert junk ads, Instagram has started to take steps to avoid creating so many superusers in the future. But, to date, it is not known to have taken any steps to ask its existing superusers to be more explicit about when they post sponsored photos, or to stop feeding the platform with so many.

And it's not just businesses that have realised the full influencing power of Instagram. An Israeli group, Once in a Lifetime (onceinalifetime.org.il), recently invited a group of 10 Instagram superusers to tour the country and take pictures – which were distributed to more than 1.5 million followers in total.

The filters so commonly seen on Instagram are even feeding back into the mainstream. A recent Sky Sports campaign featured sepia-tinged framed images reminiscent of one of the app's most popular filters.

Photography agencies are also tapping into the trend. With clients increasingly on the lookout for photos with the authenticity of imperfection, agencies are turning to non-professionals and the 250 million-plus photos uploaded every day to the internet. Some, perhaps ahead of the curve, are also seeking out the heavily processed look typical of mobile apps.

Two agencies have been set up specifically to sell mobile photos: Foap will market your best mobile photos for a flat $10, and pay you $5 if they sell; and Scoopshot allows mobile photojournalists to set their own price, then takes a commission on each sale. Both agencies seem to avoid photos with any heavy processing.

The $1bn price tag on Instagram perhaps served as a wake-up call to many businesses that there is money to be made in mobile photography. But as a young genre, it remains to be seen how money will be distributed.It also remains to be seen how Instagram will deal with the commercialisation – and potential devaluation – of its brand.

The offline world of mobile phone photography

Exhibitions As a young genre, mobile photography is still finding its own identity. Its roots may be in online and digital, but it has aspirations to be taken seriously by the rest of the photography world and various physical exhibitions have taken place. The LA Mobile Arts festival recently brought together 200 mobile artists, and a recent Instagramers exhibition in Spain was accompanied by a day of talks and presentations.

Some exhibitions are the result of competitions. One of the biggest, the Mobile Photo awards, takes its winning photos on a tour of various US cities. The iPhone Photography awards, the longest-running competition (since 2007), offers no prizes, just the prestige of winning. Instagramers London and Photobox will host an Iconic London exhibition in mid-December, accompanied by a competition to find the Photobox "motographer" of the year.

Publications There is a small body of mainly instructive literature about iphoneography, most notably iPhone Artistry by Dan Burkholder and iPhone Obsessed by Dan Marcolina, who has also just released an interactive app for the iPad with step-by-step editing tutorials and reviews of some of the key apps. High-end print magazines devoted exclusively to fine art mobile photography, such as Spain's Shooters have also started to emerge.

Forums There are dozens of daily blogs and community websites about mobile photography. One of the trailblazers, and the originator of the term "iphoneography", is iphoneography.com, which provides up-to-the-minute reviews of apps and hosts a gallery of mobile work. Instagramers.com also posts regular news of mobile photography events and developments.

Tutorials There are various recorded tutorials online, such as iPhone Camera Essentials, and several groups have organised real-time workshops. Offline, the photography department of Kensington and Chelsea College launched the UK's first five-week evening class earlier this year, and the Photographers' Gallery will be running a similar course from mid-November to mid-December.

Richard Gray teaches and writes about mobile photography (iphoggy.com). He is also a professional music photographer